When wandering through your garden, you might encounter the unexpected sight of some uninvited visitors among your plants - and we’re not talking about common birds - but wild mushrooms. Whilst these fungal formations can initially cause alarm, it’s essential to understand their role in your garden’s ecosystem.

Mushrooms are nature's recyclers, breaking down organic matter and contributing to soil health. But how do you know what species of mushrooms you have in your garden?

Keep reading as we explore how to identify mushrooms commonly found in UK gardens, address common concerns about their presence, and provide guidance on safely managing them.

Whether you're a seasoned gardener or a curious novice, understanding the relationship between mushrooms and your garden can enrich your gardening experience and keep your wildlife-friendly garden thriving.

Should I worry about mushrooms growing in my garden?

Mushrooms growing in your garden can be a bit surprising, but they are usually not a cause for concern.

Here’s four common worries that people have about mushrooms in their gardens:

1. Are mushrooms bad for my garden?

Mushrooms don't harm plants. In fact, many garden mushrooms improve soil health and support plant growth. This is because mushrooms are decomposers, meaning they break down organic matter in your soil.

Their presence often indicates that your soil is rich in organic material, which is beneficial for plants. Some mushrooms also form symbiotic relationships with plants, helping them absorb more nutrients from the soil, like phosphorus and water.

Leaving them to grow should be no reason to worry at all - in fact this practice is often known as rewilding, where you just leave your garden to do its thing. Mushrooms are a part of your garden’s ecosystem!

2. Why do I have lots of mushrooms in my garden?

Whilst the mushrooms themselves aren't generally harmful, their presence in large numbers might point to underlying issues in your garden. This could include things such as decaying wood, mulch, or poor drainage. If the decay is affecting your plants, like a dying tree root, that might need attention.

3. Are the mushrooms in my garden toxic?

Most mushrooms found in UK gardens are harmless to people and pets. If they aren't being eaten or touched frequently, there's usually no reason to worry about their presence.

However, it’s important to know that some species can be poisonous to humans and animals if ingested. If you have children or pets that might try to eat the mushrooms, it's wise to find out if your garden mushrooms are toxic, and remove them as a precaution.

4. I’m struggling to manage the mushrooms in my garden

If you prefer not to have them, or they seem to be taking over your garden, simply plucking the mushrooms from the soil won't eliminate them completely. This is because their underground fungal network (mycelium) is still present. However, they will naturally disappear as the environmental conditions (like moisture) change.

Mushrooms thrive in damp environments. If your garden has areas with poor drainage or excessive moisture, improving soil drainage or reducing watering may help limit their growth.

The basics of mushroom identification

Mushroom identification is fascinating, but it requires a lot of attention to detail since some edible mushrooms can closely resemble toxic ones. Here are the basic factors to consider when identifying mushrooms safely:

1. Cap

The cap is the top of the mushroom. Here you will want to look at its shape and texture.

Shape

Mushroom caps come in various shapes, including convex (dome-shaped), flat, bell-shaped, or conical. Some caps also have a central bump called an umbo, whilst others are smooth.

Texture

The surface texture of the mushroom can be smooth, slimy, dry, or scaly. Slime on the cap often indicates a mushroom that prefers wet environments.

2. Gills, pores, or spines

The gills, pores or spines are all located on the underside of the gap. Not all mushrooms have all three, so it’s important to be able to recognise each.

Gills

Also known as Lamellae, mushroom gills are thin, blade-like structures under the cap, where spores are produced. Their colour, spacing, and attachment to the stem (free, attached, or decurrent) are important clues to identifying a mushroom.

Pores

Some mushrooms have pores instead of gills. These pores release spores and vary in size and colour.

Spines

Also known as mushroom teeth, some mushrooms have tiny tooth-like projections under the cap.

3. Stem

The mushroom stem, or stipe, is what holds the mushroom up. Different mushrooms have varied lengths, thicknesses and textures. Some also have a ring around the stem or a volva.

Length and thickness

Mushroom stems can be tall, short, thin, or thick. Some have a bulbous base, and others are uniform in width.

Texture

The stem of a mushroom can vary. It can be smooth, fibrous, or scaly.

Ring

Also known as an Annulus, some mushrooms have a ring around the stem, which is a remnant of the veil that covers the gills when the mushroom is immature.

Volva

A volva is a sac-like structure at the base of the stem in some species. The volva is often buried underground, so digging around the base helps in identification.

4. Spore print

A spore print is the colour of the mushroom’s spores - an essential identification feature in figuring out what the mushroom is, and whether or not it is toxic. Common spore print colours include white, black, brown, purple-brown, pink, and yellow.

How to make a spore print

- Remove the cap from the mushroom.

- Place it down on a white piece of paper (and a black piece, too, for contrast).

- Cover the cap with a bowl or glass to prevent drying.

- After several hours or overnight, the spores will leave an imprint on the paper.

5. Colour

The colour of the cap, gills, stem, and spores can vary greatly between mushrooms. Pay attention to any colour changes as the mushroom ages or when bruised, as this can also help with identification.

6. Smell

Some mushrooms have a distinctive smell. For example, some species often smell fruity, whilst others may smell like almonds or anise.

7. Habitat

Where is the mushroom growing? Note if it's growing on wood, soil, or among leaf litter. This will help, as many mushrooms are habitat-specific.

8. Time of year

Certain species of mushrooms only appear during specific seasons. This will help greatly in identification.

9. Growth pattern

Observe if the mushrooms grow singly, in clusters, or in rings (also known as fairy rings). Some species are solitary, whilst others grow in groups.

12 common British wild mushrooms and how to identify them

The UK is home to a variety of wild mushrooms, and whilst some are edible and delicious, others can be toxic. Here’s a guide to 12 common British wild mushrooms, whether they’re edible or toxic, and how to identify them:

Edible British wild mushrooms

1. Field Mushroom (Agaricus campestris)

- Appearance: A white, smooth, and slightly convex cap, that may have some faint scales as it matures, and a short and white stem, with a small, thin ring around it.

- Gills: Initially pink, turning brown as the mushroom ages.

- Habitat: Found in grassy fields, meadows, and lawns.

- Season: Summer to late autumn.

- Toxicity: Highly edible, with a mild and pleasant smell, similar to typical store-bought mushrooms.

2. Giant Puffball (Calvatia gigantea)

- Appearance: A large, round white mushroom, sometimes growing as large as a football. It has a smooth surface and no gills. When mature, the inside turns to brown spore dust.

- Gills: No gills, just an internal spore mass.

- Habitat: Found in meadows, fields, and woodland edges.

- Season: Late summer to early autumn.

- Toxicity: Edible when young and white inside. As with smaller puffballs, make sure to cut it open to confirm it's not a young Amanita.

3. Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius)

- Appearance: Golden-yellow to orange, with a wavy, funnel-shaped cap and a firm, fleshy texture. The stem is solid and usually the same colour as the cap.

- Gills: Gills are more like ridges and are forked, running down the stem (decurrent).

- Habitat: Found in mossy, damp woodlands, often among conifers.

- Season: Late summer to autumn.

- Toxicity: Edible and highly prized. Has a fruity, apricot-like smell.

4. Common Puffball (Lycoperdon perlatum)

- Appearance: A small to medium-sized, pear-shaped or round mushroom. The outer surface is covered with small spines that easily rub off. When mature, the puffball releases brown spores.

- Gills: No gills; spores are produced inside the ball.

- Habitat: Found in grasslands, woodland edges, and sometimes lawns.

- Season: Late summer to autumn.

- Toxicity: Edible when young and firm, before the spores form (must be white inside). Can be mistaken for young Amanita species, so caution is advised.

5. Shaggy Ink Cap (Coprinus comatus)

- Appearance: A tall, white mushroom with a shaggy, cylindrical cap that becomes bell-shaped as it ages. The cap edges turn black and begin to "melt" into an inky liquid when mature.

- Gills: Initially white, turning black as they age.

- Habitat: Common in grassy areas, roadside verges, and gardens.

- Season: Summer to autumn.

- Toxicity: Edible when young (before the gills start turning black), but must be eaten quickly after picking as it deteriorates rapidly.

6. Wood Blewit (Lepista nuda)

- Appearance: Lavender-blue to purple cap, becoming paler with age. The stem is also lavender, and the gills are lilac, fading to buff.

- Gills: Decurrent (running slightly down the stem) and crowded.

- Habitat: Found in leaf litter in woodlands, especially in autumn.

- Season: Late autumn to winter.

- Toxicity: Edible when cooked (never eat raw). Some people can have allergic reactions, so try a small amount first.

7. Amethyst Deceiver (Laccaria amethystina)

- Appearance: A small, bright purple mushroom that fades to pale lilac as it ages. The cap is convex, and the stem is thin and fibrous.

- Gills: Widely spaced and the same purple colour as the cap.

- Habitat: Common in mixed woodlands, often found in leaf litter.

- Season: Late summer to autumn.

- Toxicity: Edible, but not highly regarded. Often mixed with other mushrooms to add colour.

- Appearance: A large, fan-shaped mushroom that grows in clusters. It has overlapping, soft, grey-brown fronds, and a white pore surface underneath.

- Gills: No gills; it has pores on the underside of the fronds.

- Habitat: Grows at the base of hardwood trees, particularly oaks.

- Season: Late summer to autumn.

- Toxicity: Edible and considered a delicacy, with a texture similar to chicken.

Toxic British wild mushrooms

9. Death Cap (Amanita phalloides)

- Appearance: An olive-green or yellowish cap, with a white stem that has a ring (annulus) and a volva at the base. The gills are white.

- Gills: Free from the stem and white.

- Habitat: Found in deciduous woodlands, especially near oak, beech, and birch trees.

- Season: Late summer to autumn.

- Toxicity: One of the deadliest mushrooms. Extremely poisonous - even small amounts can be fatal if ingested.

10. Destroying Angel (Amanita virosa)

- Appearance: A pure white, smooth cap, often convex but flattens with age, and a white stem, with a delicate ring near the top and a large, sack-like volva at the base, often buried in the soil.

- Gills: Pure white, free from the stem.

- Habitat: Found in woods, particularly near broadleaf trees.

- Season: Summer to autumn.

- Toxicity: Deadly poisonous. Contains amatoxins that can cause fatal liver and kidney damage.

11. Sulphur Tuft (Hypholoma fasciculare)

- Appearance: A small, bright yellow to greenish-yellow cap with a darker centre. The stem is also yellow, and the gills start pale but turn greenish-black with age.

- Gills: Crowded and attached to the stem.

- Habitat: Grows in clusters on dead wood, tree stumps, and fallen branches.

- Season: Late summer to autumn.

- Toxicity: Poisonous, causes gastrointestinal distress. Easily mistaken for edible species, so avoid.

12. Fly Agaric (Amanita muscaria)

- Appearance: Bright red cap covered in white warts. The cap is initially rounded, becoming flatter as it matures. It has white stem with a ring (annulus) and a bulbous base with a volva.

- Gills: White and free from the stem.

- Habitat: Often found under birch, pine, and spruce trees, in woodland areas.

- Season: Late summer to autumn.

- Toxicity: Highly toxic and hallucinogenic, not to be consumed.

13 safety tips for handling wild mushrooms

When handling wild mushrooms, especially when foraging or examining them in the wild (which includes your garden), safety should be your top priority. Many mushrooms are toxic or even deadly, and some edible varieties have poisonous look-alikes.

Here are key safety tips to follow:

1. Do not eat any mushrooms that you are not 100% sure about

Even experienced foragers can make mistakes, so if you cannot positively identify a mushroom using multiple reliable sources, do not eat it. Toxic mushrooms like the Destroying Angel and Death Cap can look very similar to edible species.

2. Avoid eating raw wild mushrooms

Some mushrooms that are edible when cooked are toxic when raw. Always cook wild mushrooms to destroy any potential toxins.

3. Wear gloves

When handling unknown mushrooms, wear gloves to avoid skin contact with potentially toxic compounds. Some people may experience skin irritation or allergic reactions from touching certain mushroom species.

4. Carry mushrooms in a breathable container

Use a basket or a paper bag to store mushrooms whilst foraging. Avoid plastic bags, as they cause mushrooms to sweat and degrade, potentially encouraging the growth of harmful bacteria or mould.

5. Handle only one Mushroom species at a time

Mixing different species in your basket can lead to accidental ingestion of toxic varieties. Keep different mushrooms separate to avoid confusion.

6. Check for toxic look-alikes

Many edible mushrooms have dangerous look-alikes. Be thorough in your identification process. You should also cross-reference your findings with reliable sources.

7. Know the habitat and season

Many mushrooms grow in specific environments or seasons. Knowing where and when certain mushrooms grow can help with identification.

8. Keep children and pets safe

Children and pets may be curious about wild mushrooms and could accidentally ingest poisonous ones. Teach them not to touch or eat mushrooms they find in the wild, and supervise them during outdoor activities.

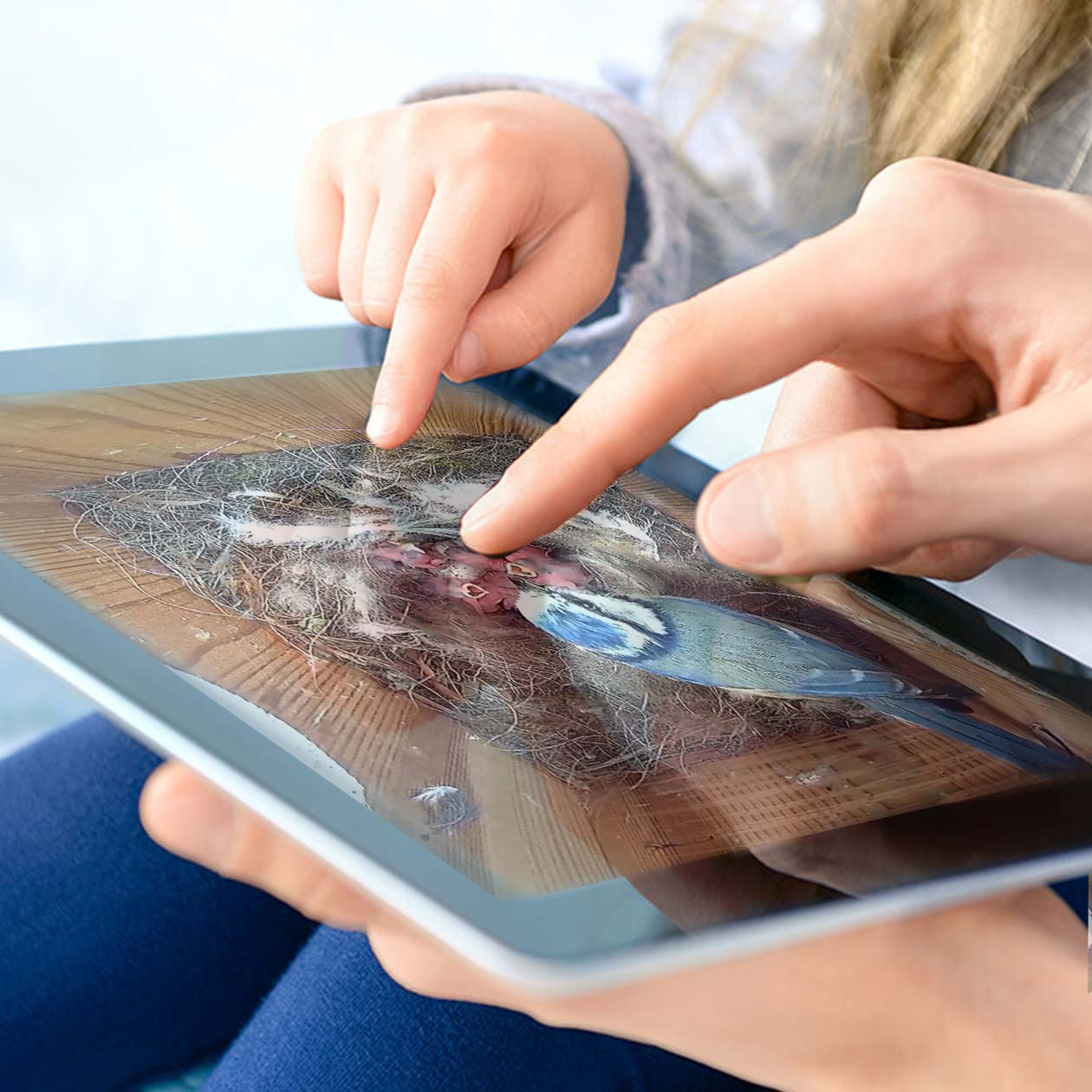

9. Take photos before handling or harvesting

If you’re unsure about a mushroom, take clear photos from multiple angles (cap, gills, stem, and habitat) to help with later identification or to consult a mycologist (mushroom expert).

10. Taste testing is dangerous

The old method of tasting small amounts of mushrooms to identify them is highly dangerous. Even tiny quantities of some toxic mushrooms can be fatal. Never taste an unidentified mushroom.

11. Consult local mycologists or foraging experts

If you’re new to mushroom foraging, or have simply just found some in your garden, consider joining a local mushroom hunting group or consulting a mycologist (mushroom expert) to learn how to identify species safely.

12. Use multiple identification sources

Don't rely on just the knowledge in this post, a single book or an app to identify mushrooms. Cross-reference information from several sources, such as reputable field guides, online forums, or knowledgeable individuals.

13. Be aware of symptoms of poisoning

Even if you follow all these tips perfectly, you should still be aware of the signs of mushroom poisoning. These can include:

- Nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea

- Abdominal pain

- Dizziness, confusion, or hallucinations

- Delayed liver or kidney damage (as in poisoning from Amanita species)

If you suspect mushroom poisoning, seek immediate medical attention and, if possible, bring a sample of the mushroom for identification.

How to remove mushrooms from your garden

Removing mushrooms from your garden can be a simple process, but it's important to understand that they are the fruiting bodies of a larger underground fungal network (mycelium). Whilst you can remove the visible mushrooms, eliminating the entire fungus may be challenging.

Here's how you can remove and manage mushrooms effectively in your garden:

1. Pluck or rake the mushrooms

The most straightforward way to remove mushrooms is to pick them by hand or rake them. Wear gloves to avoid direct contact, especially if you're unsure about their toxicity. You can also cut mushrooms at the base using garden scissors or a knife. This prevents them from releasing more spores into the garden.

After removal, do not compost the mushrooms, as this could help spread the spores. Instead, discard them in the trash.

2. Reduce moisture

Mushrooms thrive in damp, moist environments. Reduce the frequency of watering to allow the soil to dry out between waterings - especially in shady or low-lying areas. If your garden has poor drainage, consider adding organic material like compost or sand to improve the soil's ability to absorb and drain excess water.

You should also ensure that garden hoses, irrigation systems, or any drainage systems are not leaking or over-watering certain areas.

3. Remove organic debris

Mushrooms feed on decomposing organic material such as dead roots, wood chips, mulch, or decaying leaves. Removing or replacing this organic debris can reduce their food source.

If you have a thick layer of mulch, consider raking it to dry it out, or replacing it with fresh mulch if it's heavily decomposed. Switching to inorganic mulch (like stones or gravel) may also help reduce mushroom growth.

4. Aerate the soil

Aerating compacted soil can help reduce mushroom growth, by improving airflow and drying out the soil. Use a garden fork or an aerator to create small holes in the soil to encourage better oxygenation and water drainage.

5. Apply nitrogen fertiliser

Applying a nitrogen-rich fertiliser can speed up the decomposition of organic matter in the soil, which is what mushrooms feed on. This reduces the chance of mushrooms continuing to grow. However, be careful not to over-fertilise, as that can harm your plants.

6. Remove tree stumps and roots

Mushrooms often grow on decaying wood, including buried tree stumps, roots, or logs. If possible, remove old stumps or roots that could be feeding the fungal network beneath your garden.

7. Increase sunlight

Mushrooms thrive in dark, shady environments. Pruning trees or hedges to allow more sunlight into the garden can help to reduce mushroom growth by drying out the soil.

8. Use fungicides as a last resort

Whilst fungicides are available, they are not always effective against mushrooms, as they only target the visible parts and not the underground mycelium. However, in cases of persistent fungi problems, applying a fungicide to infected areas may help manage outbreaks.

Some gardeners prefer natural antifungal options like diluted vinegar or baking soda solutions, though their effectiveness varies.

9. Prevent future growth

Rake fallen leaves, grass clippings, and plant debris regularly, as these materials can become a food source for fungi if left to decompose. As soon as you see new mushrooms, remove them immediately before they mature and release spores.

Interested to learn more about all the different things than go on in your garden? Contact us today for advice on how to reconnect with your outdoor wildlife, or explore our blog for more garden insights.

Really appreciate the insights you’ve shared in this post—it’s rare to find such well-researched and UK-specific cannabis content. As someone passionate about promoting quality products and education in this space, I found it especially valuable. Keep up the great work! For anyone interested, we’re also sharing helpful info and top-shelf products over at https://thcandvapes.co.uk/—feel free to check us out!

Really appreciate the insights you’ve shared in this post—it’s rare to find such well-researched and UK-specific cannabis content. As someone passionate about promoting quality products and education in this space, I found it especially valuable. Keep up the great work! For anyone interested, we’re also sharing helpful info and top-shelf products over at https://thcandvapes.co.uk/—feel free to check us out!

Really appreciate the insights you’ve shared in this post—it’s rare to find such well-researched and UK-specific cannabis content. As someone passionate about promoting quality products and education in this space, I found it especially valuable. Keep up the great work! For anyone interested, we’re also sharing helpful info and top-shelf products over at https://thcandvapes.co.uk/—feel free to check us out!